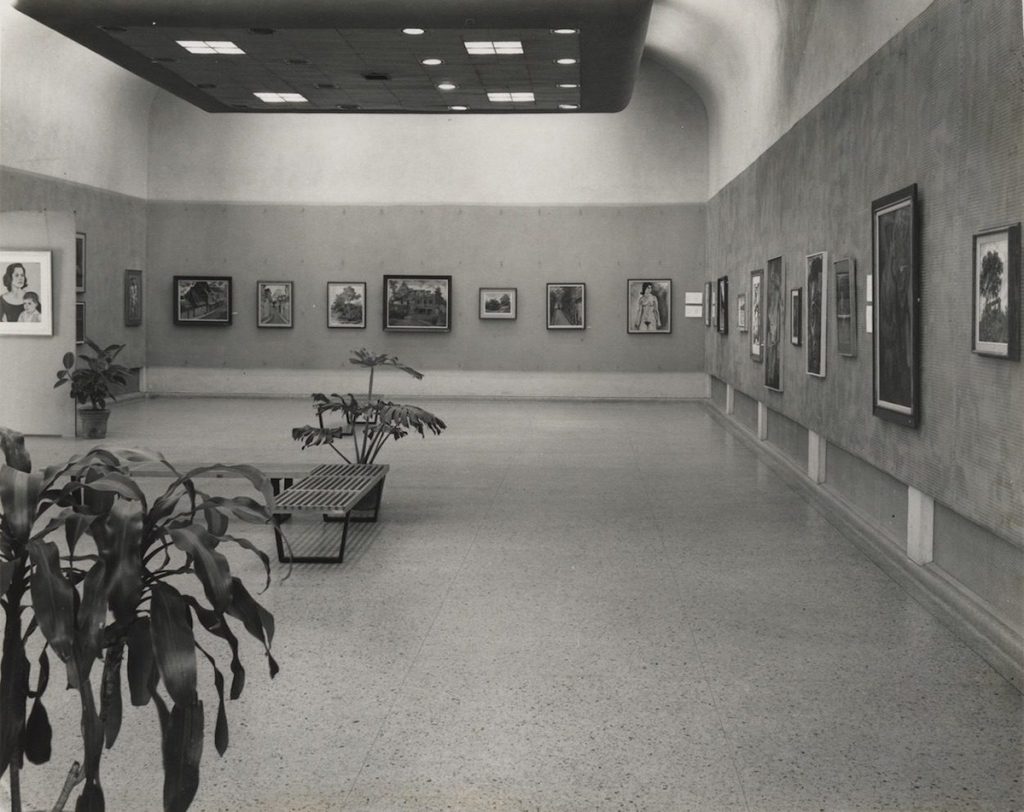

Arana Paintings and Drawings exhibition, August 6, 1963.

[spacer height=”20px”]Every civilized society needs an awareness of the past, a sense of tradition, in order to endure and prevail. One of the most effective ways of achieving this objective is through museums. The most valuable spiritual expressions of those who came before us are preserved within them; they are, to a large extent, the source from which the creations of the future are to emanate.

Nilita Vientós Gastón, “La creación de un museo,” Diario de Puerto Rico, March 19, 1949

[spacer height=”20px”]History

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there were various instances in which different people, concerned about the cultural enrichment and development of the country, considered the need to create a national museum to foster the development of the fine arts and their conservation. However, no project was carried out in Puerto Rico (Ramírez de Arellano 8).1

[spacer height=”20px”]

The University of Puerto Rico, founded in 1903, received its first art collection in 1914 from the holdings of Federico Degetau, our first resident commissioner in Washington, D.C., and a man devoted to the humanities and culture who always dreamed of creating a picture gallery on the island.2 At this point, the existence of a museum on campus was not even a consideration. With this ultimate objective, Degetau had amassed a collection of paintings from his travels in Europe. Among the works of art were pieces by Ana María Degetau, Federico Degetau, Horace Vernet, Sofía, Adolfo Marín Molinas, Mercedes Vives, Antonio Cortés Rolón, Pilar Bermejo, and other unattributed works.

When the collection was delivered to the university, it was exhibited in the building where the Academic Senate is now located. However, for many years the works were also displayed on classroom walls and in university offices.3

[spacer height=”20px”]

The renowned painter Francisco Oller y Cestero, aware of the value of these works, proposed to organize a museum to house the collection. In a correspondence, he commented that he would endeavor “to direct it with no salary of any kind,” since “it would be good for the country; many students would go there to collect impressions comparing some works of art to others; there they would see different talents and copy them as they wish, as it so happens in museums.” (Delgado 142). A year later, in 1915, his painting El Velorio (The Wake, 1893), which up until then was exhibited in the Biblioteca Insular, was moved to the University of Puerto Rico for its safekeeping.

Trina Padilla de Sanz, known as the “daughter of the Caribbean,” who was interested in all forms of art, wrote the article “Mi propósito” (My Determination) in 1918 after the painter Óscar Colón Delgado was not granted a scholarship he applied for from the Legislature of Puerto Rico to study abroad. On this occasion, she also advocated for the creation of the museum:

We should stop focusing on projects and start doing something practical. Here, everything gets started, without ever setting down roots. Everything becomes a patriotic fuss without any ultimate good being reported, and so things that could positively be of general interest for the country simply come to a halt. We should promote the arts and fund a conservatory, for we have very proficient music teachers; establish a museum for paintings and sculptures, and what is properly initiated can be joined together as one. With this, we shall create more of a homeland, [leaving aside] personal disputes […].

The idea of creating a museum to house the works donated to the University was proposed in the development plan of this institution, which was presented by the architectural firm Bennet, Parsons & Frost in 1925. A library, a museum, and an auditorium were originally planned around the central courtyard (Moreno, “La arquitectura de la Universidad” 36). However, the museum project was never launched, being eternally postponed due to other priorities.

In 1926, Rafael W. Ramírez de Arellano4 was hired by the University of Puerto Rico to serve as a professor in Puerto Rican history. In his classroom (room 9 in the Felipe Janer building), he set up a small museum with objects, historical documents, maps, paintings, engravings, newspapers, and archaeological artifacts that he had collected to use as supplements and illustrations in his courses. As the collections expanded, the idea to found a museum on campus also attracted greater interest. According to Ramírez:

[spacer height=”20px”] [spacer height=”20px”]The University, as the pinnacle of the education system in Puerto Rico, as an official institution of the State, and as an educational institution that has people with the necessary academic preparation to disseminate human knowledge, was the ideal and logical location for the museum we dreamed of. (8)

In tandem with Professor Ramírez’s museum, exhibitions were held at the university beginning in 1929. They were managed and organized by American professor and artist Walt Dehner.5 The first exhibition was titled An Arts and Crafts Show by Faculty and Students of the Art Department, held in the Baldorioty building. His enthusiasm and interest for the arts led him to organize other exhibitions: First Exhibition of Puerto Rican Art and History (November 15 to 18, 1929), in which paintings from the Degetau collection and from the Juan Ponce de León Museum were displayed along with works from various other artists, and historical objects; Second Exhibition of Puerto Rican History and Art (January 14 to 18, 1931); Exhibition of Etching and Lithography, the first traveling exhibition of works on loan to appear on the island (April 1931); Progressive-Conservative Show of Contemporary American Art (November 4 to 7, 1931); Black and White Show of Modern Art (March 17 to 20, 1932); Exhibition of Modern Catalan Painting (April 2 to 9, 1933); Third Exhibition of Puerto Rican Art (December 1933), in which more than 300 works were submitted as part of a competition; Exhibition of the Restored Works from the Degetau Collection (May 19 to 20, 1935) by Franz Howanitez (Lee 81-83)6; Exhibition of Contemporary Mexican Art (January to February 1935); First Independent Exhibition of Puerto Rican Art (December 1 to 21, 1936); Walt Dehner Exhibition (November 1 to 27, 1937); and Exhibition of Peruvian Art (1938).7 All of these exhibitions set a precedent at the university, further sparking an interest in the establishment of a museum.

Little by little, the university received other donations that increased its collections. In 1935, it received a portrait of Juan José Osuna by Franz Howanietz8, and another one of Juan González Chávez by Francisco Oller y Cesteo.9

In 1935, the collection in Classroom 9 was moved to the basement of what is today known as the Antonio S. Pedreira building in the university. It was there where the Juan Ponce de León Museum was inaugurated in 1939 (Font 2-3, 63-64). The collection remained at this humble location until 1943, when it was transferred over to the Chancellor’s Office. That same year, the university received a donation from the Fernández Náter family, which included Oller’s self-portrait—which the artist had given to Manuel Fernández Juncos—and a bronze statue of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza by Julio González Pola. Other families were encouraged to repeat this gesture (“Gesto digno de ser emulado”).

[spacer height=”20px”]Beginnings of the Museum of History, Anthropology and Art

The university administration officially recognized the museum in 1943, and it was placed under the direction of the College of Humanities. A year later, the collections were transferred to the first floor of the university library. In 1947, the museum’s governing body saw some changes. Anthropologist Ricardo Alegría was appointed assistant director, and the museum was divided into three sections: Anthropology, managed by Alegría; History, managed by Ramírez; and Art, managed by Professor Osiris Delgado and Sebastián González García, dean of the College of Humanities. That same year, Alegría organized an archaeological excavations project in Puerto Rico, which yielded many findings (“El Centro de Investigaciones” 4).10 In October 1947, the exhibition of Puerto Rican Archaeology saw its inauguration.11 It was organized exclusively with the archaeological artifacts unearthed during the excavations in Luquillo and Loíza. It included the following sections: Historical Sources for the Study of the Island’s Indigenous Groups, Stratification of Cultures in Luquillo, Personal Adornment, Child Burials, Indigenous Skulls, Indigenous Burials, The Decorative Art of Ceramics, Conch Use, Indigenous Ceramics, Tools Used by Indigenous Groups, and Distribution of Indigenous Cultures during European Exploration.

Nineteen hundred forty-eight was a pivotal year for the history of the museum; it was the year when the exhibition of Francisco Oller 1833-1917 was held. It took place after the end of a strike at the university that same year.12 Oller’s masterwork The Wake was exhibited there, along with other works loaned by collectors. An exhibition of forty-one paintings by José Campeche was held in the exhibition gallery in the College of Humanities.13 The University Board approved the construction of the Archaeological Research Center, which was put under the direction of the museum, in June 1948 (“El Centro de Investigaciones” 4). That same year, the design of the future museum was commissioned to the architect Henry Klumb.

Alegría launched a publicity campaign aimed at attracting donations of objects in order to expand the museum’s initial collection.14 Due to this initiative, various people donated their collections, especially those of an archaeological nature. The most prominent donors included Rafael W. Ramírez, Gildo Massó, Benigno Fernández García, José Limón de Arce, Josefina M. de Acosta Velarde, Herman Ferré, Alejandro Tapia, Amparo Fernández Náter, Carlos de Castro, Ramón López Prado, Nan de Antonsanti, Emilio Pasarell, Carmen Marrero, and Adolfo de Hostos.

In March 1949, Senator Rubén Gaztambide Arrillaga introduced a bill (House Bill 371) to earmark $80,000 for the construction of the museum (Ramírez Brau 4, 24). Several articles were published with this goal in mind.15 An excerpt from one of them reads:

The project for a museum for Puerto Rico is not new […] Contrary to popular belief, museums are not simply a place to store, collect, and categorize historical, anthropological, and art pieces that are more or less valuable or intriguing. No. Museums are the hearts of the expansion and creation of culture. They are the centers that foster and strengthen the productive power of the human imagination. They are the seat and shrine in which a people’s tradition is deposited in an aesthetic, historic, and humanist fashion, meticulously arranged so that our collective intellect and sensibilities may have a complete picture of what was, thereby enabling us to excel in the future. (“Un museo para Puerto Rico”)

Nilita Vientós Gastón, president of the Ateneo Puertorriqueño (a vital Puerto Rican cultural institution), supported the bill introduced by Senator Rubén Gaztambide Arrillaga for the creation of the Museum of History, Anthropology and Art at the University of Puerto Rico. She wrote:

Every civilized society needs a sense of tradition if it is to endure and overcome its conscience of the past. One of the most effective means to this end is the museum. They preserve the most valuable spiritual expressions of those that preceded us; they are, to a large extent, the source from which future creations must emanate. Creating some forms of art in a country without museums is an almost impossible undertaking… (“La creación del museo”)

Another of the published editorials offers the following insight:

Will the negligence and disregard that our government has shown hitherto in facing this culture problem ever be transformed into warm and generous attention? Will the time come when the arts in Puerto Rico enjoy the unwavering support that they merit by virtue of their effective contribution to improving the lives of our people? Will a vigorous arts promotions program to raise the cultural level and enrich the sensitivity of Puerto Ricans be organized? These are the questions that the government and Puerto Rican society must answer if we are to forge, for the benefit of present and future generations, a better Puerto Rico.16

The Puerto Rican senate did not pass the bill. In 1950, it was introduced with amendments, but it was rejected yet again. A year later, it was reintroduced, as PR House Bill 846 (P. de la C. 846). Thanks to countless efforts and tireless work, on April 15, 1951, the legislature approved Bill 97 (Proyecto de Ley Núm. 97), aimed at turning the university museum into a national museum. This law establishes that the museum would function under the auspices of the University of Puerto Rico and its purpose would be “to collect, maintain and preserve, for the purpose of research and cultural dissemination, all that which constitutes a part of our historical, anthropological and artistic heritage.” Furthermore, it declared that the museum would be constructed on the grounds of the university.

[spacer height=”20px”]

However, the project was not assigned the necessary budget for construction. On June 13, 1955, Governor Luis Muñoz Marín signed PR House Resolution 92 (H.R. 92) into law, thus assigning $150,000 to the University of Puerto Rico for the design and construction of the first stages of the Museum of History, Anthropology and Art (“Gobernador interino firma diez proyectos” 4)

As early as October 1950, the museum had inaugurated a series of exhibitions focusing on anthropology, history and art.17 The art section included an exhibition of Puerto Rican painters and another of popular imagery.

The exhibition galleries were restored years later and were inaugurated on August 19, 1955.18 The museum had three sections, each with its own thematically arranged displays. The first one was the anthropology section, which comprised an exhibition gallery of Puerto Rican archaeology and another of archaeological excavations. The second one, the history section, displayed exhibition galleries on the conquest and colonization of Puerto Rico, the historic site of Caparra, the weapons of the conquest, Caribbean cartography, scenes from Puerto Rico, eight eminent Puerto Ricans, and cultural history, which included European prehistory and Egyptian archaeology. This section also displayed historical periods and events, such as slavery, the libreta system, the abolition of slavery, the Lares uprising, the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico’s autonomous period, the civil government under the Jones Act, political cartoons, the first Puerto Rican commission in Washington D.C. under U.S. rule and the Jones Act. The third was the art section, which was inaugurated with the exhibition Dos siglos de pintura puertorriqueña (Two Centuries of Puerto Rican Painting) and comprised prints, a room of Puerto Rican popular music, popular music instruments, popular imagery, craftwork, and objects from the festivities of St. James the Apostle, held in the coastal town of Loíza.19

In April 1957, the museum opened two new permanent exhibition galleries: one for contemporary painting and sculpture and another for prints (Rivera 5). The rooms remained open until June 1958.

The new museum building began construction in 1957 (“Adjudican obra para Museo UPR” 7). Architect Henry Klumb designed it to be built in five phases.20 However, only a quarter of the original design was built.21 The new building officially opened to the public on June 4, 1959, with an exhibition that showcased artworks by Francisco Oller y Cestero.

For years, construction and remodeling at the museum came to a standstill. In 1990, a proposal was submitted to the Ford Foundation for the rehabilitation of the art collection storage area. This proposal sought more spacious and adequate areas for storage, a temperature control system, an exhibition processing space, and new offices. It was accepted, and the architecture firm Bermúdez y Calzada was put in charge of the design. In June 1993, remodeling work began on the eastern area of the museum.22 An additional contribution from the university allowed for the construction of a two-story module to house the administrative offices. This module, officially opened in 1995, emulates the height of the exhibition gallery to maintain the harmony of the building.

In 1999, when the remodeling of the permanent archaeology exhibition gallery was set to begin, the western walls of the museum began to crack as a result of the excavation that was carried out to construct the UPR train station of the metropolitan area train system (Tren Urbano), which is located only twenty feet away from the walls of the museum building. The architect in charge of the project, Manuel Bermúdez, decided to cease operations until the construction of the station was completed. However, by then, the cost of reconstruction had increased considerably due to the damage caused to the building, and the university was already facing other budgetary priorities.

The American Alliance of Museums (AAM) initiated the accreditation process of the MHAA in 2004, which included the development and implementation of a plan to comply with its accreditation standards. These standards are related to Public Trust and Accountability, Mission and Planning, Leadership and Organizational Structure, Collections Stewardship, Education and Interpretation, Financial Stability, and Facilities and Risk Management. In 2012, the MHAA hosted the AAM’s on-site visit. The final report noted that the university would be granted a year to decide what actions to take concerning the building. On August 2, 2013, after numerous requests—first to the Board of Trustees and thereafter to the Board of Governors—the Board of Governors of the University of Puerto Rico approved Certification Number 3 (2013-2014), whereby they agreed to amend the Permanent Improvements Program, Certification Number 115 (2010-2011), to incorporate and authorize the Museum’s improvements project. For the project’s implementation, Dr. Ethel Ríos Orlandi, then interim chancellor of the Río Piedras Campus, stipulated that half of the project’s costs would be financed with institutional funds. The remaining costs would be paid with funds from the UPR Central Administration and from insurance compensation for the Río Piedras Campus. The MHAA was accredited on October 31, 2013, becoming the third museum on the island, and the first university museum, to obtain such accreditation. The reconstruction works commenced in August 2018.

[spacer height=”20px”]Collections

The art collections of the MHAA reflect the evolution of holdings that, assembled gradually over the course of several administrations, offer an exemplary overview of different artists, periods, and mediums. Today, the MHAA’s collections exemplify our country’s cultural and artistic richness and constitute an invaluable legacy to be preserved, studied, and exhibited for the benefit of present and future generations. We wish to underscore the importance for the museum of the donations of works of art by artists, collectors, institutions, and individuals who appreciate our cultural heritage and seek to have it preserved for posterity.

[spacer height=”20px”]Paintings, Drawings, Watercolors

The artworks in the Paintings Collection offer a rich and extensive view of the development of Puerto Rican art from the eighteenth century to the present. The pieces have been amassed over the years by way of acquisitions and through donations by artists and collectors. The collection includes ten paintings by José Campeche y Jordán (San Juan 1751-1890) and his family workshop. There are also nineteen works of art by Francisco Oller y Cestero, including his masterwork El Velorio (The Wake, 1893), an impressive large-scale canvas that has become an icon of the MHAA. Oller himself donated it to the University in 1915. This painting is an extraordinary visual record of the traditions of a rural social class of nineteenth-century Puerto Rico. Other artists in the Paintings Collection include Manuel E. Jordán, Julio Medina González, José Cuchy, José López de Victoria, Lorenzo Homar, Rafael Tufiño, Carlos Raquel Rivera, Myrna Báez, José Antonio Torres Martinó, Félix Rodríguez Báez, Luis Hernández Cruz, Alfonso Arana, Oscar Mestey Villamil, Julio Rosado del Valle, Carlos Marcial Torres, Augusto Marín, Oscar Colón Delgado, Manuel Hernández Acevedo, Luisa Géigel Brunet, and José Meléndez Contreras.

In recent years, we have received paintings donated by Jaime Romano (12 paintings), the Estate of José Trías Monge (39 pieces),23 Francisco Vizcarrondo Terrón (2 paintings) and Angelita Rieckehoff (4 works). During the period of 2016 – 2018, we accepted three donations of paintings belonging to Dr. Eduardo Rodríguez, which are of great importance to Puerto Rican art history. Among the artists in that collection are Carlos Raquel Rivera, Librado Net, Lorenzo Homar, Francisco Oller, Adolfo Marín Molinas, Manuel Castaños, Jorge Morales Zeno, Juan Felipe Ríos, and Oscar Colón Delgado. In December 2018, we received a donation of 17 works of art belonging to collectors Radamés Peña Radamés Peña Plá and his wife, Lizette Biaggi Valladares, which include paintings by Carmelo Sobrino, James G. Shine, Antonio Maldonado, Ángel Botello, Arnaldo Maas, Amalia Cletos Noa, José López de Victoria, Domingo García, José M. Dobal, and Horacio Castaign. The Drawings and Watercolors Collection consists of 582 works of art, among which are pieces by artists such as Librado Net, Manuel E. Jordán, Marta Pérez, Rafael Ríos Rey, Carlos Marichal, John Balossi, Julio Rosado del Valle, Carlos Raquel Rivera, Rafael Tufiño, Joaquín Reyes, Cristóbal Ruiz, Enrique T. Blanco, Mario Brau, Walter Dehner, Marta Pérez García, Augusto Marín, Lionel Ortiz, Martín García Rivera, and Isabel Bernal. The collection is also the repository for several artists’ notebooks.

International Graphic Arts Collection

The Museum holds a significant sampling of approximately 700 international prints. Of these, 170 were purchased from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1954 by Jaime Benítez, Esq., then chancellor of the Río Piedras Campus. The arrival of these prints at the university coincided with his concept of la casa de estudios [house of studies], which encouraged people to become familiarized with the great works of the Western world, including the visual arts (Moreno, Grabado y literatura 7). Furthermore, these prints by international artists arrived in Puerto Rico at the outset of an ongoing tradition of printmaking as a multiple work of art, one that is accessible to all.

Benítez began conversations with MoMA in 1953, when he requested a collection of photographic reproductions of masterpieces to be shown in the museum’s exhibition gallery for educational purposes with the aim of promoting the visual arts on the island. This initiative resulted from the challenges the University of Puerto Rico was facing in offering its students direct contact with international art due to its geographical location and lack of accessible collections. In a letter sent to Benítez in September of 1953, Monroe Wheeler, MoMA’s director of exhibitions and publications, remarked that in addition to the requested collection, he deemed it important for the university to acquire a small selection of original prints by well-known modern artists for a modest fee. Benítez agreed with the recommendation, and thus Wheeler (1899-1988) and William Lieberman (1923-2005), director of the Prints Department since 1949, moved forward with curating the collection. MoMA had numerous duplicate copies that could contribute to forming a valuable collection for our institution.

Wheeler visited the university in November 1953, at the invitation of Benítez, to meet Puerto Rican artists and to offer a conference titled The Art of Our Time to commemorate the inauguration of the campus’s exhibition space. He also established a partnership program that allowed the Río Piedras campus to benefit from the traveling exhibitions which MoMA offered to universities and art centers across the United States and abroad. As part of this program, the university organized various exhibitions, such as Original Graphic Works by Picasso (September 1 – September 15, 1954) and Twenty-Five American Prints (February 28 – March 13, 1957). In 1955, with the collection acquired from MoMA, Marc Chagall Graphic Works (February 18 – March 7) and Original Graphic Works (March 26th to April 15th) were presented in the University’s exhibition space.

This collection consists of selected graphic works from the fifteenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, even though most of the collection dates from the first half of the twentieth century. A large number of European artists had suffered the horrors of the First and Second World Wars. Nazism also censored the creations of avant-garde artists beginning in 1934, whose works they deemed “degenerate.” In their place, the national art scene exalted Greco-Roman Classicism, the greatness of Germany alongside its myths and the concepts of heroism and labor. Well-known artists and writers, along with other intellectuals, professors, critics, and gallery owners sought exile in the United States, particularly in New York City, which evolved into the epicenter of the abstract art movement. Toward the end of the 1930s the Museum of Modern Art, as well as the Whitney Museum and the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (which would later become the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum) began to feature exhibitions that centered on Cubism, abstract art, Dadaism and Surrealism, seeking to familiarize the American public with the European avant-garde movements of the time. This led to a great segment of the population learning about the work of many artists who had emigrated to this city. The United States government granted emergency visas to artists such as Max Beckmann, Massimo Campigli, Marc Chagall, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Fernand Léger, Gabor Peterdi, Bernard Reder, Piet Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, George Grosz, Josef Albers, André Breton, Stanley William Hayter, and Walter Gropius, given that they were regarded as intellectual refugees who would culturally enrich the country. Having been important figures in the European art world, many of them went on to work as professors in art schools and universities, which in turn benefited students and supported the development of the American contemporary art scene.

The collection acquired by the University of Puerto Rico includes artists from the United States, as well as Mexico (David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera and Rufino Tamayo). Many of the works are lithographs printed between 1950 and 1953. During the war, very few artists produced graphic works due to the fact that they lacked the necessary materials or equipment. After World War II, there was a resurgence of this art form, especially in the field of lithography, etchings, and woodcuts, since there were still many masters in these fields willing to print the work of artists. A great many of the works of the collection organized by MoMA were printed in workshops renowned for the quality of their productions, such as Guilde Internationale de la Gravure (Adam, Campigli, Ernst, Marini, Tamayo), Éditions les Quatre Chemins (Clavé, de Chirico) and the Roger Lacourière studio in Paris (Hartung, Singier, Soulages), the International Graphic Arts Society (Baskin, Reder) and Rio Grande Graphics (Moy, Peterdi).

In addition to encompassing diverse subjects and approaches, some of these works were produced to illustrate books, others were inspired by literary themes, or were portraits of famous writers.24 The artists represented in the collection include Leonard Baskin, Massimo Campigli, Marc Chagall, Giorgio de Chirico, Antoni Clavé, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Erich Heckel, Aristide Maillol, Henri Matisse, Gabor Peterdi, Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Georges Rouault, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Rufino Tamayo. Over the years, many exhibitions have been mounted to showcase this collection. The works are preserved for academic purposes, to supplement the university’s art history courses, and for future generations to enjoy.

Another section of this international collection consists of prints purchased between 1968 and 1971 by Jorge Enjuto, who was the dean of Humanities during that period. For the most part, these were acquired in Europe not to form part of the museum’s collection, but to be exhibited in classrooms and offices so as to promote an environment where employees, students and professors could be in direct contact with original works of art. Many of the works were purchased from European artists, such as Ricardo Baroja, Bernard Buffet, Luis Fernández Noseret, Manuel Hernández Mompó, as well as from Latin American artists such as Antonio Frasconi, Alberto Peri, Juan Downey and José Luis Cuevas. Gradually, these works have been transferred to the museum by the offices where they were originally displayed.

The collection has grown over the years through acquisitions and donations. Some of the high points include The Disasters of War by Francisco de Goya, a print series that was acquired in the 1960s; El Portafolio Latinoamericano (The Latin American Portfolio), funded by Galería Colibrí; Portafolio AGPA, Dragons (2003) and Beasts (2003), which were coordinated by the Mexican graphic artist Artemio Rodríguez and published by La Mano Press. The most recent international acquisition is the Portafolio Lorenzo Homar: Cuban Graphic Tribute, organized by Casa de las Américas (Havana), which consists of 23 graphic works in various techniques, which was donated to the museum in 2014.

[spacer height=”20px”]Puerto Rican Graphic Works

This collection was initially organized in the 1960s, during a pivotal decade for a movement focused on experimentation and promotion of the visual arts. The opening of new galleries in San Juan contributed to the advancement of Puerto Rican artists. Galería Colibrí, an art space that focused exclusively in its early years on the exhibition and sale of Puerto Rican graphic works, is perhaps the most noteworthy of these galleries.

The MHAA’s holdings of graphic artworks were also acquired by direct purchase from artists or galleries, over different periods, and by donations. The collection consists of approximately 1,900 works that reflect the wide range of graphic production in Puerto Rico from the 1950s until the present. The most renowned artists in the medium are represented in the collection, including Lorenzo Homar, Rafael Tufiño, Carlos Raquel Rivera, José R. Alicea, José Antonio Torres Martinó, Carlos Marichal, Myrna Báez, Antonio Martorell, Manuel Hernández Acevedo, Consuelo Gotay, Rafael Rivera Rosa, John Balossi, Luis Alonso, Jesús Cardona, Domingo García, Martín García Rivera, Manuel García Fonteboa, Rolando López Dirube, Maritza Dávila, Susana Herrero, Luis Hernández Cruz, María Emilia Somoza, Antonio Maldonado, Carlos Irizarry, Dessie Martínez, Augusto Marín, José Meléndez Contreras, Oscar Mestey, Orlando Salgado, Sixto Cotto, Lizette Lugo, Poli Marichal, Ida Nieves Collazo, José Rosa, Juan Sánchez, Néstor Millán, Dennis Mario Rivera, Nelson Sambolín, Luis Maisonet Ramos, José Peláez, Francisco Rodón, Joaquín Reyes, Omar Quiñones, Noemí Ruiz, Isabel Vázquez, Irene Delano, Víctor Rodríguez Gotay, Nora Rodríguez Vallés, Carmelo Sobrino, Elsa Meléndez, Zinthia Vázquez, Garvin Sierra, Carlos Rivera Villafañe, Ada Rosa Rivera, Marta Pérez, Anna Nicholson, Melquiades Rosario Sastre, Omar Velázquez, and Carlos “Sueños” Ortíz.

Nearly all techniques and mediums are represented: screen printing, woodcut, linocut, etching, lithography, woodblock prints, zincography, Plexiglas, digital printing in molds or engraving plates donated by the artists. Among the molds, we can find those that were donated by Lorenzo Homar, in linoleum and wood; other works in wood where donated by Marcos Irizarry, Melquiades Rosario Sastre, and Rafael Rivera Rosa. In 2015, Myrna Báez donated 29 plates of her engravings in collagraphy, linoleum, metal, and Plexiglas. The museum also received a donation of linoleum plates from the artist José A. Torres Martinó through the Torres Martinó Estate. This group of objects is extremely important for students studying the process of engraving, beginning with the plate, and then moving onward to the final print.

A selection of portfolios by various artists is also included, such as the first and second portfolios of The Center for Puerto Rican Art; La Plena by Rafael Tufiño, and Plenas by Lorenzo Homar; Los casos de Ignacio y Santiago (The Cases of Ignacio and Santiago) by José Meléndez Contreras and Rafael Tufiño; El Mirador Azul (The Blue Lookout); the first portfolio of The Ateneo Puertorriqueño; The Abolition of Slavery portfolio (1973);Three Stanzas of Love for Soprano by Lorenzo Homar; Luto absoluto (Absolute Grief), Nocturno rosa (Glowing Evening), Las moscas (The Flies), Las Barajas Alacrán (The Scorpion Cards), and Catálogo de objetos (Catalogue of Objects) by Antonio Martorell; Cuaderno de un retorno al país natal (Homecoming Notebook), Hay un país en el mundo (There is a Country in this World), A Door into Time in Three Voices, Salmos del cuerpo ardiente (Psalms of the Sultry Body), and ¿Puedes? (Can You?) by Consuelo Gotay; Desahucio (Eviction), and Medianía Alta by Luis Alonso; Lorenzo Homar: Tributo gráfico puertorriqueño (Puerto Rican Graphic Tribute), by a variety of Puerto Rican artists: De Olimpia a Mayagüez (2010) (From Olympia to Mayagüez) by Nelson Sambolín and donated by Bernard Friedman, among other works.

The artwork produced in Puerto Rico by highly skilled engravers has set the stage for a rich artistic tradition that continues to bear fruit through the works of young artists.

[spacer height=”20px”]Poster

Since its beginning, the poster has transcended its importance as an aesthetic object to reaffirm itself as a testimony to Puerto Rico’s cultural and social commitment. Concerts, exhibitions, festivals, carnivals, arts and crafts, fairs, theater and dance performances, contests, sports, educational messages, and political events form an eloquent backdrop to the tremendous range of human activity reflected in the thematic content of posters.

Puerto Rican artists have produced such a vast number of posters that it would be impossible to consider any collection complete or authoritative. However, given the size of the MHAA poster collection, with more than 6,000 works from the 1940s to the present, we do feel that it is certainly representative. The collection was formed over the years almost entirely by donations from artists, institutions, and collectors, reflecting social, economic, cultural, artistic, and political struggles and realities. The major Puerto Rican poster artists, from 1949 to the present, are represented in the collection, as well as those posters created in studios and workshops, both public and private, including The Public Parks and Recreation Commission’s Taller de Cinema y Gráfica (Puerto Rican Division of Community Education / DIVEDCO), the Center for Puerto Rican Art (CPRA), the Taller de artes gráficas of the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture (IPRC), the Taller Galería Campeche, the Taller del Museo de la UPR, the Taller de Actividades Culturales of the University of Puerto Rico, in addition to Alacrán, El Seco, Bija, El Jacho, Visión Plástica, Tiburón, Guaní.

The most important poster donations were made by the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). In 1999, this firm donated 1,900 works through the collaboration with Dr. Teresa Tió.25

Many aspects of Puerto Rican social, political, and cultural realities can be analyzed by studying the development of this artistic medium, which emerged initially in the 1940s. For this reason, in 2014, the MHAA submitted a proposal to the National Endowment for the Humanities to digitize and upload to the internet 4,000 posters from the collection. The initial phases of the project, involving photography and digital imaging, have been completed, and the information has already been integrated into the collection management system. The Museum System (TMS) made the collection even more readily accessible through the eMuseum app in August 2019. Global access to the MHAA poster collection on the museum’s website is now a reality, thereby enabling greater access to this invaluable collection for education and research purposes.

As a result of the digitization project, over the past four years the museum has received more than 700 posters, donated by the artists or their families. Among these are the family of Lorenzo Homar, Rafael Rivera Rosa, Luis Abraham Ortiz, Antonio Martorell, the family of Sixto Cotto, Myrna Arocho, María García Vera, Elsa María Meléndez, Zinthia Vázquez, Fernando Santiago, Ismael Hidalgo, Roberto Tirado, Eliasim Cruz, Consuelo Gotay, Anna Nicholson, María Antonia Ordóñez, Juan Sánchez, Ángel M. Vega, Luis Maisonet Ramos, Luis Torres Tapia, Nelson Sambolín, Ángel Pérez, Dennis Mario Rivera, Osvaldo De Jesús. Other posters were donated by collectors Dennis Simonpietri, Margarita Fernández Zavala, and Francisco López Romo as well as institutions such as the Narciso Rabell Foundation (2014), the Chess Federation of Puerto Rico (2015), the Pablo Casals Museum, the Dr. Pío López Martínez Museum of Art, the Division of Artisanal Development, the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture, and the Inter American University of Puerto Rico.

[spacer height=”20px”]Sculpture

This is the museum’s smallest collection. The MHAA has a limited number of sculptures from artists such as Julio González Pola, Antonio Navia, Melquiades Rosario Sastre, Rafael Ferrer, Francisco “Compostela” Vázquez Díaz, George Warreck, John Balossi, Ramón Berríos, Carmen Inés Blondet, Luisa Géigel, Arnaldo Morales, and Antonio Prats Ventós. In 2016 the family of Francisco “Compostela” Vázquez Díaz donated 16 of his penguin sculptures to the museum as well as drawings, memorabilia, sketches, and other documents pertaining to the artist to be kept at the Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center.

[spacer height=”20px”]Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center and Library

The Center is where original artist documentation such as correspondence, photographs, catalogues and exhibition invitations, magazine and newspaper clippings, and albums are kept dating from the 1930s to the present. During recent years, the MHAA has received priceless document collections from organizations and artists which are particularly relevant for research on the history of Puerto Rican art. These donors inlcude the Hermandad de Artistas Gráficos de Puerto Rico, Myrna Báez, José Antonio Torres Martinó, Francisco “Compostela” Vázquez Díaz, José R. Alicea, Botello Gallery, and Lorenzo Homar. The collection of documents consists of the portfolios of artists, galleries and institutions, records of the exhibitions organized by the MHAA since its inauguration as well as other resources. The Center also houses books relating to museum studies, artists’ notebooks, publications on Puerto Rican art and many other subjects. Access for research purposes is available by appointment.

Exhibitions

Since its early days, the Museum has organized numerous painting, print, solo, group, and themed exhibitions as well as history and anthropology exhibitions. Renowned international and local artists have presented their work in the exhibition gallery. Themed art exhibitions, spanning from the seventeenth century to the present, have dealt with and analyzed important Puerto Rican cultural issues. Some of the more important exhibitions include Pintura hispanoamericana en Puerto Rico (Hispano-American Painting in Puerto Rico, 1976); Orfebrería en Puerto Rico (Metalwork in Puerto Rico, 1977); Artes de la Villa de San Germán (Art From the Villa de San Germán, 1978); Personajes de Rodón (Rodón’s Subjects, 1983); El cartel en Puerto Rico 1950-1985 (The Poster in Puerto Rico 1950-1985, 1985); La xilografía en Puerto Rico 1950-1986 (Woodcut Prints in Puerto Rico, 1986)26;La estampa serigráfica en Puerto Rico 1946-1987 (Screen Printing in Puerto Rico 1946-1987, 1987); De Oller a los cuarenta: La pintura en Puerto Rico 1898-1948 (From Oller to the Forties: Painting in Puerto Rico 1898-1948, 1988); Imágenes de Hostos a través del tiempo (Images of Hostos Through Time, 1988); Arnaldo Roche Rabell, Eventos, milagros y visiones (Arnaldo Roche Rabell: Events, Miracles and Visions, 1986); Marcos Irizarry: 26 años de obra sobre papel 1960-1986 (Marcos Irizarry: 26 Years of Works on Paper 1960-1986, 1987); Puerto Rican Painting: Between Past and Present (1988); Betances entre nosotros (Betances Among Us, 1989); Navia, Suárez, Rosario, tres escultores contemporáneos (Navia, Suárez, Rosario: Three Contemporary Sculptors, 1989); Domingo García, Iconos de nuestra historia (Domingo García: Icons of Our History, 1991); Exlibris: El libro como propuesta estética (Exlibris: The Book as a Work of Art, 1994); Alto riesgo, Electrobjetos de Arnaldo Morales (High Risk, Electro-Objects by Arnaldo Morales) (1996); Abrapalabra, la letra mágica: Carteles de Lorenzo Homar (Abrapalaver, The Magic Letter: Posters by Lorenzo Homar, 2001); La Cultura Saladoide en Puerto Rico: su rostro multicolor (The Saladoid Culture in Puerto Rico: Its Multicolored Face, 2002); Carlos Marichal, poeta de la línea (Carlos Marichal: Poet of the Line, 2002); Cien años de historia, arte y enseñanza (One Hundred Years of History, Art and Education, 2003); Ballajá, arqueología histórica de un barrio de San Juan (Ballajá: The Historical Archaeology of a Neighborhood in San Juan, 2004); La imprenta en Puerto Rico; Cultura La Hueca (Printing in Puerto Rico; La Hueca Culture, both in 2005); Autocontemplación, autorretratos en pintura (Self-Contemplation: Self-Portrait Paintings, 2006); Taínos, objetos ceremoniales (Taínos: Ceremonial Objects, 2007); De la pluma a la imprenta: La cultura impresa en Puerto Rico 1806-1906 (From The Pen To The Printing Press: The Culture of Printing in Puerto Rico 1806-1906, 2008); El Grito de Lares (2011); Francisco “Compostela” Vázquez Díaz (2011);Museum Circle by John Cage (2012); El Velorio ahora (The Wake Now, 2012); Tradiciones en transición (Traditions In Transition, 2014); Premios de la Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano y del Caribe (The San Juan Biennial Latin-American and Caribbean Graphic Art Awards, 2015); Reflejos de la historia de Puerto Rico en el arte (Images of Puerto Rico in Art, 2016); Ida y Vuelta, experiencias de la migración en el arte puertorriqueño contemporáneo (Departures and Arrivals: Migratory Experiences in Puerto Rican Contemporary Art, 2017-2018); and José R. Alicea: espejo de la humanidad (José R. Alicea: Mirror of Humanity, 2018-2019).27

[spacer height=”20px”]

Most of these exhibitions also featured a brochure and/or catalogue, the product of research conducted by the curator, which now serve as indispensable reference materials for art history students and scholars. These texts are essential for constructing a comprehensive understanding of Puerto Rican art history.

Some of the awards received by the MHAA for its exhibitions and catalogues include those conferred by the International Association of Art Critics, Puerto Rico chapter, such as Individual Exhibition, Local Artist for Alto Riesgo by Arnaldo Morales (1996); Historical Exhibition for Hispanofilia (1998); Installation by Sylvia Benítez (1997); Art book by Domingo García (1999); Dissemination of the Arts by a Cultural Institution (2001); Individual exhibition for Abrapalabra: La letra mágica, Carteles de Lorenzo Homar (2001); Optimus, Excellence Award for Lorenzo Homar’s catalog (2002); Book for Abrapalabra research (2001); Exhibition of the Year for Carlos Marichal: poeta de la línea (2003); Art Book for Carlos Marichal, poeta de la línea (2004); Best History Exhibition for Cultura La Hueca (2005); Collective Local Artist Exhibition for Autocontemplación (2007); Installation Design for La Cultura Saladoide; and the Curatorial Award for Museum Circle by John Cage (2012).

MHAA Directors

The chronological list of directors of the museum, each of whom have left their own significant imprint on the institution’s development, includes Ricardo Alegría (1947-1955), Osiris Delgado (1955-1975), Rafael Rivera García (Interim Director), Arturo V. Dávila (1976-1984), Carmen Ana Pons (1979-1980), Mari Carmen Ramírez (1984-1988), Annie Santiago de Curet (1988-1994), María Luis Moreno (Interim Director), Luis Hernández Cruz (1995-1999), Iván Méndez (Interim Director 1999-2000), Petra Barreras (2000-2001), Ginette Alomar (2001-2002), Flavia Marichal Lugo (2002 to the present).

Since its inception, the Museum of History, Anthropology and Art has contributed to the development of our culture through an educational program, offered not only to the university community but to all Puerto Ricans. The scheduled events include exhibitions, workshops, conferences, guided tours, and access to collections. The MHAA has set important precedents in the history of museums in Puerto Rico, playing an exemplary role for museums that were to follow. It is an invaluable resource for the process of understanding and analyzing our historical origins and the fundamental characteristics of our national identity.

[spacer height=”20px”]The Museum of History, Anthropology and Art is located at the University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras Campus. Its regular hours are Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday from 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., Wednesdays from 8:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m., and Sunday from 12:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Closed on holidays. Entry is free of charge. For more information, you can call (787) 763-3939, or you can write to us at museo.universidad@upr.edu.

[spacer height=”20px”]Translated by the students of the Translation for Museums class, Graduate Program in Translation, UPR-RP

Edited by David Auerbach

[spacer height=”20px”]

Notes:

1. For more information, please consult the dissertation of Luz Elena Badía Rivera. Historia de los museos de Puerto Rico, 1842-1959: Musealizando su patrimonio y narrando la identidad. University of Granada, 2017. http://hdl.handle.net/10481/48522

2. See Rafael Sacarello, “El sueño de un prócer, nuestro museo de Bellas Artes,” El Tiempo, January 16, 1924, pp. 3-4. Originally, this collection was a part of the Rosa Cruz Museum Library, which Degetau had organized in Aibonito, and which consisted of 159 paintings and 18 graphic artworks. “La colección Degetau,” in Osiris Delgado Mercado, Francisco Oller y Cestero (1833-1917) (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Centro de Estudios Superiores de Puerto Rico y el Caribe, 1983), p. 143.

3. See “Lista de las oficinas de la UPR en que están distribuidos los cuadros restaurados de la colección Degetau,” MHAA Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center. In 1976, there were still several paintings left on the walls of some offices, which were transferred for safekeeping to the MHAA storage facilities. Currently the collection comprises 91 artworks.

4. Rafael W. Ramírez de Arellano (San Germán 1884-San Juan 1974) began his professional career as a public school teacher. In 1912, he was appointed as a Spanish instructor at the College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts in Mayagüez. In the 1920s, he transferred to the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus, where he taught the same subjects as and dedicated his time to researching folklore. In 1926, he enrolled in the Centro de Estudios Históricos para la Ampliación de Estudios in Madrid. Appointed shortly thereafter as a History professor at the University of Puerto Rico, he spent more than thirty years as a lecturer of Puerto Rico’s history, leaving an indelible mark as a promoter of historical research in the country. He also contributed to fostering interest in this field among a group of disciples who later became major scholars in the field of History, such as Arturo Morales Carrión, Ricardo E. Alegría, Luis M. Díaz Soler, Arturo Santana Peña. Professor de Arellano founded and directed El Mes Histórico magazine, and published several installments on historical documentation. He is credited with the following works: Folklore puertorriqueño: cuentos y adivinanzas recogidas en la tradición oral (1926), Cómo vivían nuestros abuelos (1957), Cuentos folklóricos (1957), La última tarde (evocación histórica) (1964), and Historia de una calle. Upon his retirement from the University of Puerto Rico in 1951, he was awarded the honorary title of professor emeritus by the History Department (UPR-RP). Subsequently, for several years he worked as the official historian for the city of San Juan. At the time of his death, he served as the director of the Museo de la Familia, a cultural center under the auspices of the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture, which awarded him the National Culture Prize in 1965. See “Rafael Ramírez de Arellano,” Revista del Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, No. 66, January – March 1975, pp. 1-2.

5. Walt Dehner (Buffalo, NY 1898-1975): An American painter, lithographer, and photographer. He was one of the artists hired to teach art in Puerto Rico between 1930-1946. His contributions were considerable as a promoter of Puerto Rican art and culture. He completed his BA at the University of Illinois and his MA at the University of Ohio. He also studied at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and at the Art Students League of New York, where he studied under the Social Realist painter George Bellows (1882-1925) and with Eugene Speicher (1883-1962). He arrived in Puerto Rico in 1929. In 2018, the MHAA received five artworks by Dehner as a donation from Dr. Eduardo Rodríguez.

6. The paintings from the Degetau collection had been damaged by the hurricanes that hit the island: Hurricane San Felipe (1928) and San Ciprián (1932) which destroyed parts of the university’s buildings. Mr. James R. Bourne, director of the Emergency Relief Administration of Puerto Rico (PRERA), made it possible for the restoration of the collection under the care of the Viennese restorer and artist Franz Howanietz. See “La colección Degetau: un proyecto importante de restauración de arte efectuado en la Universidad de Puerto Rico,” in Muna Lee de Muñoz Marín, ed. Art in Review, Reprints of Material Dealing with Art Exhibitions directed by Walt Dehner and Acquisitions in the University of Puerto Rico, 1929-1938. The University of Puerto Rico Bulletin, series XIII-No. 2, Dec. 1937, pp. 81-83.

7. For additional information on the subject, see Muna Lee de Muñoz Marín, editor. Art in Review, Reprints of Material Dealing with Art Exhibitions directed by Walt Dehner and Acquisitions in the University of Puerto Rico, 1929-1938. The University of Puerto Rico Bulletin, series XIII-No. 2, Dec. 1937.

8. The location of this artwork is unknown.

9. See “Un retrato de don Juan González Chávez por Oller” in La Democracia, May 6, 1936, reprinted in Muna Lee de Muñoz Marín, editor. Art in Review, Reprints of Material Dealing with Art Exhibitions directed by Walt Dehner and Acquisitions in the University of Puerto Rico, 1929-1938. The University of Puerto Rico Bulletin, series XIII-No. 2, Dec. 1937, p. 196. Currently, this artwork is part of the MHAA collection.

10. The Archaeological Research Project was the predecessor of the Archeological Research Center.

11. See the brochure for the Puerto Rican Archaeology exhibition at the MHAA Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center. These exhibitions were designed by Mela Pons de Alegría, Ricardo E. Alegría, and Luis Muñoz Lee. The background of the Culture Stratification in Luquillo and Indigenous Burial, was painted by Cristóbal Ruiz, art professor at UPR-RP.

12. That year, Chancellor Jaime Benítez denied access to Pedro Albizu Campos at the university theater. Albizu Campos had recently arrived from his imprisonment in the United States. According to the chancellor, Albizu did not possess the intellectual “qualifications” to give a presentation at the university. Benítez shut down the university due to violent confrontations with the police and the arrests of hundreds of students. The chancellor expelled numerous students and professors from the institution and banned all political activity on campus.

13. See exhibition brochure at the MHAA Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center.

14. Local newspaper articles include “Museo de la Universidad se enriquece con donativo hecho por Doctor Massó,” El Mundo, December 24, 1948, 35; “Donan objetos arqueológicos a Museo UPR,” El Mundo, October 13, 1949, 4, 22; and “Josefina Matienzo de Acosta Velarde; Valiosos donativos recibidos; se invita donar colecciones,” Universidad, April 2, 1949.

15. Published articles include Ramírez Brau, Enrique, “Proponen creación de un Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte,” El Mundo, March 10, 1949, 4, 24; Padró, Humberto, “El Museo de Puerto Rico,” Diario de Puerto Rico, March 11, 1949; “Editorial,” El Mundo, March 17, 1949; “Editorial: Un museo de Puerto Rico,” Diario de Puerto Rico, March 28, 1949; “Proyecto dispone la creación de nuevo museo de Historia en la Universidad,” El Mundo, March 28, 1950; and “Editorial: Más atención para las artes,” Puerto Rico Ilustrado, July 8, 1950.

16. This message is still relevant today since the arts have never been a priority for any administration in power.

17. Refer to Exposiciones: Antropología, Historia, Arte, 1950, also available at the MHAA Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center.

18. See brochure Inauguración de las nuevas salas, August 19, 1955, also available at the MHAA Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center.

19. The Institute of Puerto Rican Culture was founded in this year and Ricardo Alegría was appointed director. Upon Alegría’s resignation from the MHAA, Osiris Delgado took his place as director.

20. Henry Klumb’s blueprints are preserved at the MHAA Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center.

21. The museum was originally supposed to have three permanent gallery spaces (history, anthropology, and art); a library; workshops; laboratories; storehouses; offices; and a conference room. For example, the Indigenous Cultures Gallery was initially designed to house the library.

22. The offices were moved to a temporary location along the museum hallway to allow for the remodeling.

23. To see all of the work in José Trías Monge’s bequest, refer to the Colección José Trías Monge, un legado para la Universidad, MHAA, 2009 catalogue, available at the MHAA Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center.

24. For more information on this subject, see María Luisa Moreno, Grabado y literatura: gráfica internacional en la colección del Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras (Río Piedras: Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte, 1998), available at the MHAA Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center.

25. Poster duplicates from the collection were given to the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico. One of the agreements was that the Museo de Arte Dr. Pío López Martínez could use the posters for exhibitions in its Lorenzo Homar Gallery.

26. This exhibition traveled to Argentina and the Dominican Republic.

27. See the complete list of the exhibitions mounted at the museum since 1959 to the present at the MHAA Puerto Rican Art Documentation Center.

[spacer height=”20px”]

Referencias:

“Adjudican obra para Museo UPR.” El Mundo, November 16, 1956.

Delgado, Osiris. Francisco Oller y Cestero (1853-1917) Pintor de Puerto Rico. San Juan: Centro de Estudios Superiores de Puerto Rico y el Caribe, 1983.

“El Centro de Investigaciones Arqueológicas de la Universidad de Puerto Rico,” Universidad, October 20, 1948.

Font Saldaña, Jorge. “Don Rafael W. Ramírez regala un Tesoro.” Puerto Rico Ilustrado, January 27, 1940, 2-3,63-64.

“Gesto digno de ser emulado.” El Mundo, December 26, 1943.

“Gobernador interino firma diez proyectos.” El Mundo, June 18, 1955.

Lee de Muñoz Marín, Muna, ed. Art in Review, Reprints of material dealing with Art Exhibitions directed by Walt Dehner and Acquisitions in the University of Puerto Rico, 1929-1938. The University of Puerto Rico Bulletin, Series XII, No. 2, December 1937.

“Más atención para las artes,” Editorial, Puerto Rico Ilustrado, July 8, 1950.

Moreno, María Luisa. Grabado y literatura, Gráfica internacional en la colección del Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte de la Universidad de Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico: Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte, 1998.

Moreno, María Luisa. La arquitectura de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras. San Juan: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 2000.

Padilla de Sanz, Trina (La Hija del Caribe). “Mi propósito.” Puerto Rico Ilustrado, Year IX, No. 417, February 23, 1918.

“Rafael Ramírez de Arellano.” Revista del Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, no. 66, January-March 1975, 1-2. https://issuu.com/coleccionpuertorriquena/docs/primera_serie_n__mero_66

Ramírez Brau, Enrique. “Proponen creación de un Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte.” El Mundo, March 10, 1949.

Ramírez de Arellano, Rafael W. “Museo de Historia y Arte.” Universidad, August 15, 1948.

Rivera, Rurico E. “En Museo UPR inauguran salas de grabados y de escultura y pintura.” El Mundo, April 23, 1957.

Sacarello, Rafael. “El sueño de un prócer, nuestro museo de Bellas Artes.” El Tiempo, January 16, 1924, 3-4.

“Un Museo para Puerto Rico.” Editorial, Diario de Puerto Rico, March 11, 1949.

Vientós Gastón, Nilita. “La creación de un museo.” Diario de Puerto Rico, March 19, 1949.